They Locked Me In The Nursing Home. One Week Later, I Won $62 Million In The Lottery

They didn’t say, “We’re locking you in.” They said, “You’ll be safe here.” That’s the thing about betrayal—it never wears the right name. It comes dressed in love, concern, best interests.

I didn’t scream when they took my keys. I didn’t beg when they emptied my handbag and left my phone on the hallway table. I just stood there in the lobby of Rose Hill Care, trying to understand what had just happened.

My son, Thomas, kissed my cheek and said, “It’s temporary, Mom. Just until we make sure you’re okay.” Then he walked out.

I waited ten minutes, fifteen, twenty-five. Then I turned to the woman behind the desk—young, red lipstick, nursing badge that said SANDRA—and asked when I’d be allowed to leave.

She looked puzzled. “You’re checked in, Mrs. Leland. You’re a full resident.”

“I didn’t sign anything,” I said, even though my voice was trembling.

Sandra gave me a patient smile. “Your son did. He has power of attorney.”

I didn’t cry. Not then.

They brought me to Room 213. I remember because the door was chipped and the handle stuck. The bed was made too tightly, the kind of tight hospitals favor. The closet was half full—my clothes, but not all of them. A single framed picture of my late husband sat on the windowsill, a detail to make it feel like home.

Except this wasn’t home.

Home was 117 Dair Lane, the pale yellow bungalow with the creaky porch swing and the hydrangeas I’d trimmed every summer since 1984. Home was my kitchen chair—second from the end—with the worn cushion. Home was the house I’d bought with Harold, paid off with grocery store budgets and a broken wrist from waitressing through my fifties.

Home was gone, just like that.

That night, I didn’t sleep. Every thirty minutes, someone shuffled past my door. I didn’t know their names. I didn’t want to. I wasn’t staying. This was a mistake, a misunderstanding.

The next morning, I asked the nurse when I could speak to someone in charge. She said, “The administrator’s only in on Wednesdays.” It was Monday.

“I’d like to call my son,” I said.

She looked at her chart and said, “No phone privileges listed under your care plan.”

My care plan.

I wanted to laugh or scream, but I just sat on the edge of the bed and folded my hands. When you’ve raised a man who can smile while putting his own mother in a nursing home, you learn real quick that noise won’t get you anywhere.

Three days passed. No calls. No visits.

Sandra brought me a blue cardigan from my old house. She said Thomas had cleared out the closet and sent over what he didn’t want to throw out.

Throw out.

I opened the bag. One dress. A scarf. My winter coat—the one with the pocket that never zipped. That coat was older than his marriage.

“You’re lucky,” one of the women said to me in the dining room. Her name was Hilda. She was ninety and half blind. “At least your family visited. Mine left me here five years ago and moved to Arizona.”

I didn’t feel lucky. I felt invisible.

They served mushy peas and chicken that tasted like cardboard. I didn’t complain. Hilda said if you complained, they wrote you up for “mood disturbance” and made you see the therapist who smelled like cough drops and sadness.

I didn’t want therapy. I wanted my name back, my keys, my kitchen window with the chipped bird feeder.

When I asked again about the phone, Sandra said, “You can use the staff one in emergencies.”

So I did.

I dialed my son—straight to voicemail. Then I dialed my old neighbor, Jenny. She didn’t answer either. I wasn’t even sure she still lived next door. I left a message anyway.

That night, I took the winter coat and hung it on the back of the chair. The pocket sagged a little. I slipped my hand inside absently, like I’d done a thousand times at the grocery store, feeling for receipts or old wrappers.

But this time, I felt paper—thick, glossy, folded once.

I pulled it out.

A lottery ticket.

I stared at it like it had come from someone else’s life. Powerball. The numbers were filled in, black ink. The purchase date: one week ago. The same day Thomas brought me here.

I turned it over. No scribbles, no barcode scratches. Still intact.

For a long moment, I just stared at it.

Then I smiled for the first time since walking into this place. Because in that moment, I wasn’t a helpless old woman.

I was someone holding a secret.

And maybe, just maybe, that secret would change everything.

You don’t really notice how loud a place is until you’re no longer welcome to silence.

Nursing homes aren’t quiet. They’re just filled with sounds nobody responds to. Coughs behind thin doors. Television static. Slow footsteps. Someone calling out a name that never comes.

I kept the ticket in my coat pocket for three days. Didn’t tell a soul—not even Hilda. I didn’t know yet if it was real, but something about just having it lit something up inside me.

I’d been cold for so long, I’d forgotten what warmth felt like.

On Thursday, I asked Sandra again, “Can I use the phone?”

“Emergency only,” she said, without looking up from her clipboard.

“My furnace could be on fire,” I replied.

She blinked. “You don’t live in that house anymore, Mrs. Leland.”

But I did—in my head. Every night before sleep, I’d walk through it room by room in memory. The front door with the scratch from Harold’s toolbox. The kitchen tile we never fixed. The spot near the stairs where my hip used to crack going down.

You don’t live in that house anymore.

That sentence stuck to me all day like something sour.

At dinner, the peas were cold. I ate them anyway. Hilda sat across from me, mumbling about some bridge club she used to run in 1962.

“You’ve got quiet eyes,” she said suddenly, pointing her fork at me.

I glanced up. “What does that mean?”

“Means you know more than you say.”

I didn’t answer.

She was right.

I waited until the night nurse came on duty—a younger one, barely out of high school, always tapping at her phone. She liked me because I didn’t call out at night or ask for pills.

When she passed by my room at 10:45, I stood in the hallway, arms folded like I’d been waiting hours.

“Sorry to bother,” I said. “I think I left my hearing aid battery in my old coat, the big gray one. Might be in the laundry. Could I—?”

She waved me toward the front desk. “Sure, just be quick. Don’t let the alarm go off when you open the door.”

No security cameras. No lock. Just an old phone with a scratchy dial tone.

I looked up the numbers manually. First, the lottery website. The winning draw had already been posted.

I checked the date. Saturday.

My ticket matched all six numbers.

I blinked hard as if I’d read it wrong. I did it again.

Matched.

Sixty-two million dollars. Jackpot unclaimed.

I didn’t smile. Not right away. I just stood there holding the phone while the night nurse scrolled through her texts a few feet away, completely unaware that ten inches of paper in my coat pocket had just changed the entire balance of the world.

I walked back to my room slowly, like I was carrying something fragile.

And I was.

I barely slept. My mind was turning so fast it felt like it might come loose. What could I do with that kind of money? I couldn’t drive. I didn’t have my bank account. My son had control of everything.

Everything.

And yet, for the first time in months, I wasn’t afraid. I wasn’t nothing. I was holding a secret so large it could swallow this whole building and spit it out as dust.

The next morning, Sandra handed me a schedule for group bingo and a craft session. I looked her in the eye and said, “I’d like to speak to a lawyer.”

She laughed. “What? Are you suing someone?”

“No,” I said. “I just want to draft a letter.”

“Well, your son handles all your paperwork.”

“Then I want a lawyer to confirm that’s still legal.”

She frowned. “Mrs. Leland, that’s not how this works.”

“It is,” I said, “if you don’t want to be reported for financial manipulation of a senior.”

She stopped smiling.

I folded the schedule and slipped it into my pocket—the same pocket as the ticket.

Later that day, I called my son again. Straight to voicemail.

So I left a message.

“Hi, Thomas. Just wanted to let you know I found something important in my coat, something you might be interested in. Call me.”

I didn’t say anything else. Let him wonder.

That night, I sat with Hilda again. She was telling me about her fourth husband. I wasn’t listening. I was thinking about names—fake names, trust accounts, private lawyers, offshore accounts, anything I’d ever heard in movies about rich people protecting their wealth from the undeserving.

I wasn’t rich yet. Not officially. But I wasn’t helpless anymore. And that made all the difference.

He finally called back.

It was Sunday morning, just after the staff rolled in the breakfast trays. Cold oatmeal. Soggy toast. I didn’t touch it.

The phone on the wall rang. Sandra picked it up, then called down the hallway.

“Mrs. Leland, it’s your son.”

I walked slowly, not because I was tired, but because I needed those few seconds to bury the fire in my throat.

“Hi, Ma,” Thomas said when I picked up. His voice sounded too cheery, like he was performing for an audience. “I got your message. Something important, huh?”

There it was.

No “How are you?” No “Do you need anything?” Just straight to the thing he might want to get his hands on.

“I found a piece of paper,” I said evenly. “In my coat pocket from the last time I wore it.”

There was a pause.

“What kind of paper?”

“Oh, just something I forgot to throw away,” I said.

I waited.

Let the silence stretch. People always reveal themselves when you don’t rush to fill the quiet.

“Listen, Ma,” he said after a beat. “I hope you’re settling in. Everyone says this place is top-notch.”

I glanced around the hallway.

An old woman was arguing with the vending machine because it wouldn’t take her dollar. Another was asleep with her chin on her chest, forgotten by everyone.

“Yes,” I replied. “Very top-notch.”

He hesitated again.

“I know this wasn’t easy, but you have to admit it’s safer. The house had stairs. You were forgetting appointments.”

“I forgot one appointment, Thomas.”

“Well, it scared Marsha. She said you didn’t recognize her voice.”

I nearly laughed. As if forgetting your daughter-in-law’s voice is a symptom of anything other than exhaustion.

“She was yelling,” I said. “That’s why I didn’t answer. And frankly, I was tired of being spoken to like a child.”

He sighed. “I don’t want to argue, Ma. I just wanted to check in. And about that paper you mentioned—”

“I threw it away,” I lied. “Didn’t seem that important.”

A beat. Silence. Then a shift in his voice, the kind people use when they think they’re cleverer than you.

“Well, good. I was worried it might be something you didn’t understand. You know, official.”

I smiled. Not because he was right.

Because he had no idea how wrong he was.

After we hung up, I walked back to my room, closed the door, and locked it—one of the only ones on the floor that still had a bolt.

I pulled out the ticket and laid it flat on the desk. I stared at it for a long time, like it might start glowing.

Sixty-two million dollars. Still unclaimed. Still mine.

I made a list of things.

I’d need a lawyer. Proof of identity. A bank account outside of Thomas’s reach. A new will.

And most of all, time.

Time to move slowly, quietly, like someone planning an escape.

That afternoon, I skipped bingo. Sandra gave me a look.

“You okay?”

“Just tired,” I replied.

In truth, I was more awake than I’d been in years.

In the common room, someone had left a newspaper. I flipped through it. In the back pages: tiny ads—lawyers, accountants, document specialists.

I tore out one.

Consultations for elderly estate planning. Discretion guaranteed.

I memorized the number.

The next day, I waited until the front desk was distracted, then borrowed the staff phone again. I called from the stairwell.

“I’m calling for a relative,” I said. “She’s in a care home. Has some financial concerns. Power of attorney issues.”

The woman on the line paused. “We deal with that a lot.”

“I’d like to set up a meeting. Name: Elaine Matthews.”

I gave a fake one. I didn’t want anything traceable to Doris Leland yet.

“Can we do it here?” I asked.

She said they could send someone—an associate. Quiet. Discreet.

Thursday afternoon. 2:30 p.m.

I hung up and pressed the phone to my chest for a second.

It was real.

I had a meeting. A start.

That night, I sat in the dark and stared out the window. The moon was high. I wondered if Thomas had finished moving things out of my house. If he’d sold my old books, the glass teapot Harold gave me for our tenth anniversary. If Marsha had thrown out my sewing box. If they’d found the photo albums in the bottom drawer of my dresser.

They weren’t just moving me out of the house.

They were erasing me.

But not anymore.

Because somewhere inside a sealed envelope in my drawer was a winning ticket they didn’t know existed.

And I had no intention of sharing it with people who treated me like luggage to be stored.

No. This time the plan was mine.

They say old people shouldn’t have secrets.

That’s exactly why we’re so good at keeping them.

Thursday came slow. I spent the whole morning pretending to read, hands trembling a little under the blanket.

At lunch, Hilda asked why I kept looking at the clock.

“Hot date,” she joked.

“In a manner of speaking,” I said.

At 2:15, I went to the front lobby, pretending I was waiting for a delivery. The staff didn’t ask questions. By now, they assumed I was mostly harmless.

At 2:29, a dark green sedan pulled up. A man stepped out—mid-forties, neat gray suit, leather briefcase. He didn’t look like a salesman. He looked like someone used to telling people they were about to get sued.

He walked in and glanced around.

“Elaine Matthews?” he asked.

I stood. “That’s me.”

He didn’t blink.

Smart man.

We went to the back garden, a little concrete square with fake plants and rusty benches—the kind of place designed to look like fresh air on a budget.

He opened his briefcase and pulled out a pad.

“I’m Andrew Meyers,” he said. “Estate planning. Confidential consultations. You said you had a situation involving power of attorney.”

I nodded. “It was signed under pressure. My son controls everything. My house, my bank accounts, even my mail.”

“Do you know what he’s done with your assets?” he asked.

“I have some ideas.”

He scribbled something.

“We can contest the power of attorney. It’ll take time. What else?”

I paused. This was the moment.

I reached into my coat pocket and pulled out the envelope.

“I found this last week,” I said, and slid it toward him.

He opened it, looked at the numbers, checked the date, then looked up.

“Have you verified this?”

“Yes. Saturday’s draw. All six numbers. Sixty-two million.”

He didn’t blink. Didn’t whistle. Just nodded slowly.

“Does anyone else know?”

“No.”

“Do you want them to?”

“No.”

“Then we need to move quickly.”

He outlined a plan: trust accounts, blind transfers, a controlled claiming process using a law office as an intermediary. Most importantly, protection from family interference.

“I’ve done this before,” he said. “Elder clients with sudden wealth. It’s more common than you think.”

He handed me a new envelope with forms inside.

“You’ll need a secure mailing address for some of this.”

“I don’t have one.”

He thought for a moment.

“We can arrange a lockbox downtown. I’ll send the documents there. You’ll need to sign in person.”

“I don’t have a car.”

“I’ll send one. But not to the home. We’ll say it’s for a medical appointment.”

I sat back. The air felt lighter. For the first time in weeks, I wasn’t just surviving.

I was building something.

“Do you want to give any of it to your family?” he asked, not unkindly.

I shook my head.

“They left me here without a conversation,” I said. “Just took my life and wrapped it up like leftovers. I don’t owe them anything.”

“Then you’ll need a new will, too.”

“I want most of it in a trust for someone I do love,” I said. “My granddaughter.”

“Name?”

“Rosie Leland. She’s twenty-one. In college. Never asked me for a dime. Never treated me like I was a coat to hang up.”

He nodded. “We’ll make it ironclad. She’ll be protected.”

He stood, gathering his papers.

“I’ll be in touch in seventy-two hours. In the meantime, don’t tell anyone. And don’t try to claim the ticket on your own. Too risky.”

“I’m old,” I said, “not stupid.”

He smiled for the first time.

“That’s what I figured.”

When he left, I stayed on the bench another ten minutes. I needed the wind, even if it smelled like bleach and asphalt.

That night, I wrote in my notebook—the one they don’t check.

Day 13 in Rose Hill. Sixty-two million untouched. Legal plan in motion. My name is Doris Leland. But they’ll remember me as someone else.

By Saturday morning, the ticket was no longer just a possibility.

It was an asset.

Andrew called at 9:00 a.m. sharp.

A woman named Carla had verified the numbers with the lottery commission. The legal shell was ready. The claim would be filed through a specialized trust—anonymous, untraceable.

“The ticket remains your property until the payout is issued,” he said. “But from the moment the check is cut, everything goes into the trust. You’ll be listed as the beneficiary under a legal pseudonym.”

“What name?” I asked.

“Clara Whitmore,” he said. “We chose something neutral.”

Clara Whitmore.

Not a name that would raise eyebrows. Not a name Thomas or Marsha would ever think to Google.

“Where’s the money going?” I asked.

“For now, into a blind holding account. Once it’s secure, we can divide it however you like.”

“I want Rosie’s portion locked until she’s thirty,” I said. “But with access for education, housing, emergencies.”

He paused.

“I’ve never seen someone be this clear this fast.”

“I’ve had a lot of time to think lately,” I said.

What I didn’t tell him was that every night, while the others watched TV or dozed through game shows, I sat with my back straight, staring out the window and building a new life in my mind.

I knew how many zeros were in sixty-two million. I knew what it could buy and what it couldn’t. It couldn’t buy back years of being ignored. It couldn’t buy back the time Marsha made fun of my shoes at Easter, loud enough for Rosie to hear. It couldn’t buy back the birthdays Thomas forgot, or the time he didn’t show up to Harold’s funeral until everyone else had gone.

But it could buy freedom.

And that was enough.

“Expect the check to arrive within three to five business days,” Andrew said. “You won’t need to touch it. I’ll handle everything. I’ll call you Monday with further instructions.”

After we hung up, I opened my drawer and looked at the envelope again. I didn’t need it anymore.

But I wasn’t throwing it away.

It was proof—not of the money, but of what I’d done before the money came.

I’d saved myself.

That afternoon, I sat with Hilda on the patio. She was watching clouds. Her eyesight was too poor to see them properly, but she still liked to name their shapes.

“Look at that one,” she said, pointing vaguely north. “Looks like a lamb. Or a broken chair.”

“You’re not far off,” I said. “Looks like both.”

She turned to me, suddenly serious.

“You’re leaving, aren’t you?”

I didn’t answer.

“I can feel it,” she said. “People like you don’t stay in cages.”

I looked at her—Hilda, who had been stuck in Rose Hill for five years. Hilda, who had given away her savings to three stepchildren who now sent her birthday cards with no return address.

I reached over and squeezed her hand.

“If I go,” I said, “I’ll send you something real.”

“Like what?” she asked.

“Like a lawyer with a pen.”

She laughed, a dry little sound.

“That would be something.”

That evening, Rosie called. I wasn’t supposed to get personal calls, but the night nurse—the same one who’d let me use the phone—had started slipping me a little time after lights out.

“Grandma,” Rosie whispered. “Dad says he might sell your car.”

I nearly dropped the receiver.

“He what?”

“He said it’s sitting in the driveway collecting dust. That it doesn’t make sense to keep paying insurance.”

“That’s my car,” I said.

“I know. That’s why I’m calling. I didn’t want you to find out after.”

My heart tightened. It was an old sedan. Nothing special. But Harold had picked it out for me. Said it matched my hands, whatever that meant.

“I’ll take care of it,” I told her. “Don’t worry.”

“I just miss you,” she said. “It feels weird not hearing your voice every day.”

“I miss you too.”

There was a pause.

“You sound different,” she said.

“Do I?”

“Stronger,” she said.

I smiled.

“I’m getting my legs back under me.”

After we hung up, I wrote another line in my notebook.

Car being sold without consent. One more brick in the wall.

Then I tucked the notebook under my pillow and went to sleep.

I dreamed of oceans and silence and the keys to my own front door.

Let them think I’m powerless.

That was the first rule I gave myself after I found out I’d won. Never let them see me as anything but the harmless old woman they think they locked away.

Let them underestimate me. Let them forget I ever had a name of my own.

Because while they were out there redecorating my life, I was building something much quieter and infinitely more dangerous.

It’s not hard to become invisible in a place like Rose Hill. You just have to stop reacting. Don’t complain when they forget to bring your mail. Don’t flinch when someone takes your seat in the dining hall. Don’t raise your voice when Sandra gives your lunch tray to the wrong person. Again.

Just smile.

Be agreeable.

They stop looking at you.

After a while, you become part of the furniture—a coat rack with good posture. And from there, you can see everything.

I learned more in three days of silence than I ever had in seventy-nine years of conversation. Who steals from the supply closet. Who drinks in the laundry room. Who’s sleeping with the night janitor. Who forgets to give out meds and lies about it on the chart.

But I didn’t write any of it down. No point. I wasn’t planning to stay long enough to blow whistles.

I just needed cover.

Time to wait for Andrew’s call. Time to let the trust fill. Time to secure the next phase.

In the meantime, I studied my enemies.

Sandra, the day nurse, had a voice like a knife and a fondness for calling older women “sweetie” when she was irritated. I caught her snapping at a man named Clyde for ringing his call bell too many times.

“You don’t need help,” she said. “You need attention.”

Clyde hadn’t spoken to anyone since. Just stared at the wall.

The administrator, Mr. Kellerman, had a smile full of teeth but eyes that didn’t match. Every Tuesday, he brought around a clipboard asking residents to sign “quality surveys” that nobody read.

I asked him once what happened to the old library room.

“Budget cuts,” he said.

Two weeks later, I saw his name on the list of donors for the new tennis court they were building for the staff.

The game here wasn’t healing.

It was containment.

And I was done being contained.

That Friday, Thomas finally showed up.

I saw my car—my old Camry—in the lot. He’d replaced the bumper sticker that used to say SUPPORT LOCAL LIBRARIES with something that read, I’M NOT ARGUING, I’M JUST EXPLAINING WHY I’M RIGHT.

Fitting.

He walked in with that same sideways smile he always used when he wanted something.

“Hey, Ma,” he said, like we’d spoken yesterday. “You look good.”

I didn’t respond.

“I was in the neighborhood,” he added. “Thought I’d drop off some things. You’re still wearing that coat, huh? It’s warm, you know. I think Marsha boxed up a bunch of your winter stuff. Want me to bring it next time?”

I shook my head.

He glanced around.

“You getting used to it here?”

“I’m adjusting.”

“That’s good. That’s real good.”

He scratched the back of his neck—his nervous tick.

“You know,” he said slowly, “I’ve been thinking. Once the estate stuff clears up, maybe we could get that house listed. Prices are high right now. Could be smart.”

“My house?”

He shrugged.

“Well, it’s not like you’re using it.”

“I built that house with your father.”

“Sure, but come on, Ma. It’s just sitting there, and the taxes—”

“I paid those taxes for forty years.”

There was a pause. His face shifted. I saw the real Thomas flicker through—the one who hated being challenged.

“I’m just trying to be practical,” he said.

I stood.

“Thank you for visiting,” I said. “But I’m tired now.”

“Wait, Ma, don’t be like that.”

“I said I’m tired.”

He stood awkwardly for a second, then leaned in for a hug.

I didn’t return it.

As he turned to leave, I said, “Oh, one more thing.”

He stopped.

“I found something in my coat pocket.”

I watched the color drain from his face.

“You did?”

I nodded.

“A reminder.”

He tried to smile.

“That’s nice.”

“It is,” I said. “Very nice.”

And then I walked away.

Not because I was done.

But because he had no idea I was only getting started.

The lawyer came during visiting hours.

Nobody noticed.

That’s the brilliance of bureaucracy—you hide anything behind a clipboard and a polite nod, and people will hold the door for you without asking a single question.

Andrew wore a navy blazer this time. Less formal. More forgettable. No briefcase, just a folder tucked under one arm. He signed in as PASTOR WILLIAM SHARP. The receptionist even offered him a cup of coffee.

Bless her heart.

I was waiting in the TV room, pretending to watch an old rerun of Murder, She Wrote. Sandra barely glanced up as I left.

“This will just be a few minutes,” I said, loud enough for the chart to catch.

We met in the family lounge. Just a spare room with a dusty loveseat and fake ferns.

I locked the door behind us.

“Everything’s ready,” Andrew said without preamble. “The check’s been issued. Funds are secure.”

I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I was holding.

“The trust is operational. The account in your alias name is active. We’ve routed all distributions through legal intermediaries. Your identity is sealed. You’re officially Clara Whitmore now—at least on paper.”

“What’s the balance after taxes, initial legal fees, and administrative filters?” I asked.

“Forty-three point seven million,” he said.

I didn’t flinch.

“Rosie’s portion?”

He handed me a page.

“Ten million in a locked trust. The conditions you specified are baked in. She can access a housing stipend, educational costs, health emergencies. Anything outside of that requires trustee approval, which is me, per your request.”

I nodded.

“She’ll be safe.”

“And you?” he asked.

“I’ll be safer once I’m out of here.”

He didn’t smile.

“That’s next,” he said. “I’ve already started drafting the motion to revoke your son’s power of attorney, but until we serve him, we stay quiet.”

“How soon can that happen?”

He checked his watch.

“Three days, maybe four. Once he’s served, we’ll begin the challenge. You’ll need to be physically present in court. That’s where things get delicate.”

“I’m ready,” I said.

He raised an eyebrow.

“No hesitation?”

“None.”

He reached into his folder and pulled out a document.

“This is your new will,” he said. “Updated, signed by you, witnessed and notarized by my office. It invalidates any previous documents, including the one your son pressured you into signing two years ago.”

I took the paper, my real name printed in bold at the top.

I read the first few lines out loud.

“I, Doris Evelyn Leland, being of sound mind and memory, hereby revoke all previous wills and codicils—”

I stopped. It was enough.

“Anything else?” I asked.

He hesitated.

“Just one thing. I had my office do a little background check on Thomas and Marsha.”

I hadn’t asked him to, but I wasn’t surprised either.

“They’ve already listed your house with a private agent,” he said. “Unofficially. Testing the waters, as they say. Photos were taken last week. Marsha posed as your representative. The listing is set to go live Monday.”

My stomach turned—not from anger, but from a quiet confirmation.

I wasn’t crazy.

I hadn’t misunderstood.

They were actively erasing me.

“They won’t get a cent,” I said.

“They won’t,” Andrew agreed. “Because by Monday, the court will have an injunction ready. They won’t be able to touch your property or your name.”

I folded the papers and slipped them into my knitting bag.

When we stood, he paused.

“You know,” he said, “most of my clients in this situation are too afraid to act. They just want their money and a place to hide. You’re different.”

“I’m not looking for revenge,” I said quietly. “I’m looking for clarity.”

He nodded.

“And after that?” he asked.

“After that,” I said, “I disappear.”

We shook hands and he left through the garden exit.

Ten minutes later, Sandra passed me in the hallway.

“You’re chipper today,” she said.

“Had a nice visit,” I replied.

She didn’t ask with whom.

They never do.

That night, I wrote in my notebook.

Funds secured. New will signed. Power of attorney to be revoked. I am no longer under anyone’s hand.

Then I tucked the notebook away, turned off the light, and lay in bed in complete silence.

For the first time in years, the quiet didn’t feel like loneliness.

It felt like control.

They put Lillian in Room 107 because she didn’t complain when the heating failed.

The others had been transferred to warmer rooms, but Lillian—who could quote entire pages of poetry from memory—simply said, “My breath fogs up the glass. That’s enough warmth for me.”

She was eighty-four, sharp as a razor and dry as salt. A former librarian with a spine straighter than most of the staff. When she spoke, she did it like books had taught her—clearly, without wasted words.

I liked her immediately.

She’d been at Rose Hill longer than most. Four years, maybe five. She didn’t attend group sessions, didn’t do crafts, never signed up for karaoke, even when Sandra begged.

“They never ask themselves why the old stop singing,” she told me once. “They just keep handing out microphones.”

We started having tea together in the rec room. She brought her own bags.

“The ones they serve here taste like boiled socks,” she said.

I didn’t argue.

I told her my real name on the second afternoon we sat together.

“Everyone here calls me Doris,” I said. “But outside this place, my name is Clara Whitmore.”

She blinked once, then smiled.

“Fascinating.”

I told her about the lawyer, the trust, the ticket. I didn’t know why. I’d kept the secret from everyone else, even Rosie. But something about Lillian made me believe she’d carry the weight of it with me, not for me.

When I finished, she didn’t ask for details. Instead, she poured more tea.

“How does it feel?” she asked.

“Like I’m holding a loaded weapon in a room full of people who think I’m harmless,” I said.

She smiled.

“Good. Stay that way.”

From then on, we met every afternoon at three. I’d bring the crossword. She’d bring her tea. We didn’t always talk about the money. Sometimes we talked about her daughter, who hadn’t called in eighteen months. Sometimes we sat in silence, listening to the radio from the common room next door.

One day she said, “You know what they don’t understand about us?”

“What?” I asked.

“We’ve had lives. Real ones. People think we were born old—that we existed just to give birth to them, lend them money, and disappear quietly into padded furniture. But we remember everything.”

I nodded.

She looked at me.

“So, when do you leave?”

“Soon,” I said. “The legal challenge goes through next week. After that, I disappear. New identity. New place.”

She tapped her teacup.

“You’ll send me a postcard.”

“I’ll send you a lawyer,” I said.

She grinned.

“That’s better.”

That Friday, Sandra caught me humming in the hallway.

“You’re in a mood,” she said suspiciously.

“I remembered something nice,” I replied.

“Well, hold on to it,” she sighed. “We’ve got a group inspection coming. Kellerman wants everyone smiley.”

“I’ll give them a smile,” I said. “Right after they fix the heating in Room 107.”

She rolled her eyes.

“Lillian doesn’t mind.”

“She shouldn’t have to,” I said.

I walked away before she could reply.

That night, Lillian and I played a secret game.

“What would you do if they gave you the keys?” I asked.

“Move to a town where nobody knows my name,” she said. “Change my hair, buy a cat, live above a bookstore, and never speak unless I felt like it.”

“You always speak when you feel like it,” I said.

“Then I’d finally stop explaining myself,” she replied.

She looked at me.

“And you?”

“I’d buy a little house near the water,” I said. “Make tea in the mornings. Eat what I want. Sleep when I want. And I’d never, ever ask for permission again.”

Lillian raised her teacup.

“To the day no one asks where you’re going,” she said.

We clinked mugs.

That was the last night I saw her.

The next morning, her door was closed. By lunch, a nurse came in quietly and took her name tag off the door. No announcement. No ceremony. No explanation.

Just gone.

Like a chapter torn from a book no one finished reading.

I asked what happened.

“Peacefully in her sleep,” someone whispered.

I sat in the rec room, staring at her empty chair. No one else seemed to notice. Or maybe they did and had learned to keep walking.

That night, I wrote only one line in my notebook.

Lillian’s gone.

And now I’m even more certain I have to get out before they forget I was ever here too.

I sent a car to my old house.

Not a taxi. A black Mercedes S-Class, windows tinted, chrome polished to a mirror’s edge. The kind of car people like Thomas couldn’t ignore.

It arrived at 4:05 p.m. on a Tuesday—the exact time Marsha usually posted her curated life updates to Instagram. Family dinners. Renovation progress. Inspirational quotes about “gratitude.” None of which ever seemed to include the woman who paid off their mortgage.

The driver got out in a crisp gray uniform and handed Marsha a white envelope. No return address. No logo. Just her name.

Inside was a letter typed on thick linen paper from a fictional company called Riverside Estate Consultants.

It said:

Dear Mrs. Leland,

Our firm represents an anonymous client with interest in acquiring several legacy properties in the Green Lake area. Your current residence at 117 Dair Lane was identified as a high-value target due to its historical registration and structural condition.

Our client is prepared to offer $1.3 million cash pending a clean title and expedited close. This is not a formal contract but an expression of serious interest. A full inspection will be arranged upon your agreement to discuss further.

Respectfully,

Riverside Estate Consultants

There was a phone number at the bottom, rerouted through Andrew’s office.

The bait was simple and delicious.

Two hours later, the phone in my room rang.

It was Rosie.

“Grandma, are you sitting down?”

“I’m always sitting down.”

She laughed nervously.

“Okay, so Mom got a letter today. Some real estate company wants to buy your house, like, urgently. All cash. A million three. Dad’s freaking out. They’re trying to figure out who this anonymous client is. He thinks it’s someone from the city trying to flip it.”

I said nothing.

“You don’t seem surprised,” she said slowly.

“I’m not,” I said. “People value things differently when they think they can profit.”

There was a pause.

“Did you do this?” she asked.

I smiled.

“Let’s just say some people need a reminder that not everything is theirs just because they’re standing on it.”

That night, Thomas called. He left a message. I played it three times.

“Hey, Ma. I know we’ve had our differences lately, and I just—I think it’d be good to talk. Maybe clear the air. I know you’re probably upset about the house stuff, but maybe we can figure something out. Call me, okay?”

He sounded uncertain. Hesitant.

Good.

For the first time since Harold died, my son was learning what it felt like to be on the outside of something important.

I didn’t call back.

Instead, I asked the nurse to help me print out a letter.

“Do you have a printer?” I asked sweetly.

“Sure,” she said. “What do you need?”

“Just a quick personal document. For a birthday.”

She didn’t question it.

I typed slowly, deliberately.

To whom it may concern,

I, Doris Evelyn Leland, am of sound mind and not under duress. I have not authorized the sale of 117 Dair Lane to any party. Any representations made by third parties acting on my behalf are false and subject to legal dispute. All inquiries regarding this property must be directed to my legal representative.

Signed,

Doris Evelyn Leland

I folded it, placed it in an envelope, addressed it to the fictional Riverside Estate Consultants.

Then I slipped it into my drawer where I kept the real documents—the ones that mattered.

This one was just theater.

But sometimes theater is the only way to make the audience finally pay attention.

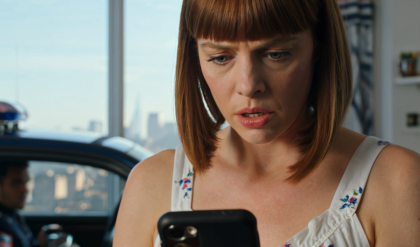

The next morning, Rosie called again.

“Dad’s losing his mind,” she whispered. “He keeps saying something doesn’t add up.”

I didn’t respond.

“Grandma.”

“Yes, dear.”

“Are you angry?”

I thought for a moment.

“No,” I said. “I’m awake.”

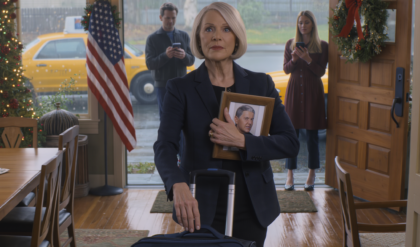

They came crawling.

It was a Friday afternoon, just after lunch, when Sandra appeared at my door with a smile she couldn’t quite keep straight.

“You’ve got visitors,” she said, with that tone people use when they’re pretending to be happy for you.

Thomas and Marsha stood in the hallway like royalty forced to walk through the servants’ wing. Thomas had a blazer on, one he never wore unless something needed presenting. Marsha wore heels and a smile so wide I knew she’d practiced it in the car.

“Mom,” he said, stepping forward like we’d spoken yesterday. “Look at you. You look great.”

“Do I?” I asked.

“Of course you do,” Marsha chimed in. “So elegant. I love that scarf.”

It wasn’t a scarf. It was the top of an old sweater I’d cut to hide a bleach stain. But sure, let her perform.

They sat across from me in the visitor’s lounge. Someone had set out those stale butter cookies no one ever eats.

Thomas crossed his legs, cleared his throat.

“I just want to start by saying we’ve been thinking about you a lot,” he said.

I nodded.

“We realize we maybe moved too fast, you know, with the house and the transition here.”

Transition—as if being locked in a nursing home was the natural next phase after buying two cans of soup in the wrong aisle.

Marsha leaned in.

“We just want what’s best for you.”

“You’ve made that very clear,” I said.

They exchanged glances.

Thomas tried again.

“Look, about that letter—the one about the house. You didn’t mention anything about wanting to sell.”

“Because I don’t,” I said.

“Right,” he said quickly. “That’s fine. Totally fine. We’re just trying to understand who might have—”

“I didn’t ask for it,” I said. “But I wasn’t surprised.”

Marsha shifted in her seat.

“Still, it’s not a great time to keep it empty,” she said. “The market’s unpredictable, and—”

“I’m not dead,” I said.

They both froze.

Marsha tried to laugh.

“Oh gosh, of course not. We just—”

“I’m not dead,” I repeated. “And this is still my life.”

There was a long silence.

“No one’s saying otherwise,” Thomas said finally.

“But you acted otherwise,” I replied, “when you emptied my closets. When you cut off my bank access. When you signed my name to things I never read. When you sold the piano.”

That last part landed. I saw it. He hadn’t expected me to know about the piano.

I leaned forward, my voice steady.

“You thought I’d go quietly. You thought I’d be grateful. You thought a tidy room and a bowl of soft peas was all I needed.”

Thomas opened his mouth. Closed it again.

Marsha smoothed her dress.

“We didn’t mean to hurt you,” she said.

“Of course not,” I said. “You were too busy helping yourselves.”

She flinched.

Thomas stood.

“Okay, Mom. We don’t have to do this right now. We just came to say hi, to check on you. Maybe bring some things from the house if you want.”

“Bring the car,” I said.

He blinked.

“My car. The one you said you were thinking of selling. Bring it back.”

“I—it’s in use,” he stammered. “We needed it.”

“It’s registered to me.”

He tried to smile.

“Technically, yes.”

“Then technically, it’s theft,” I said.

Marsha stood too.

“Maybe this was a mistake,” she muttered.

I looked up at her.

“Not on my part.”

They left ten minutes later, rattled but trying not to show it. Sandra watched them walk past the front desk, all polite nods and tight smiles. Then she turned to me.

“Family visits always so cheerful,” she said.

“Only when they’re trying to hide something,” I replied.

That evening, I sat by the window and watched the wind move through the trees like it had something urgent to say.

I didn’t move. Didn’t smile. Didn’t feel victorious.

Just ready.

One more thread had been pulled. The unraveling had begun.

He came alone the next time.

No Marsha. No pretense. Just Thomas holding a paper bag with something warm inside and a look on his face like he was walking into a courtroom, not a care facility.

“Brought you your favorite,” he said, lifting the bag. “Liver and onions from that diner you like.”

I let him place it on the table. Didn’t touch it.

He sat across from me again. This time, no blazer. Just that green pullover he used to wear in college—the one that made his eyes look softer than they really were.

“I’ve been thinking about what you said,” he began.

I said nothing.

“You’re right about a lot of things. About the house. The way we handled things.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“Handled?”

He nodded slowly.

“We didn’t mean to shut you out. We just panicked, I guess. After the doctor said there were memory issues and that thing with the stove.”

“I didn’t forget the stove,” I said. “I said the knob was broken. And the memory issues were fatigue from grief.”

He looked down.

“We made decisions we thought were smart,” he said.

“No,” I replied. “You made decisions that were convenient for you.”

He swallowed.

“I guess that’s fair.”

We sat in silence for a long moment. He shifted in his seat, hands clasped between his knees like a schoolboy waiting to be punished.

“Mom,” he said. “What did you mean when you said you found something in your coat?”

Ah. There it was.

I waited. Let the question float in the air like a feather he hoped would land softly.

“I mean exactly what I said,” I replied. “I found a reminder that what’s mine is still mine. That I haven’t disappeared. That I still have a name and choices and teeth.”

He gave a nervous laugh.

“Teeth?”

“Metaphorical,” I said.

He nodded.

“Okay.”

There was something in his face. Not guilt, not quite. Something closer to confusion—as if the script he’d written for me was no longer working, and he didn’t know how to improvise.

“Do you need anything?” he asked. “Money, clothes? I know we packed fast.”

“I don’t need a thing,” I said. “Everything I need is already in motion.”

That one hit him. I saw it—a flicker of something behind the eyes. Fear, maybe. Or suspicion.

He cleared his throat.

“You’ve always been strong, Mom, but if you ever need help, I’m still—”

“You’re not,” I said quietly. “Not anymore.”

He looked away, then, as if remembering something rehearsed, added, “Marsha wants to apologize, too. She didn’t mean to be forceful.”

“She meant to win,” I said. “She just didn’t expect me to get back up.”

Thomas stood. The bag of liver and onions still sat on the table between us, cooling.

“I’ll leave that here,” he said.

“Give it to Hilda,” I replied. “She still eats like she believes in miracles.”

He hesitated.

“Are we okay?” he asked.

I tilted my head slightly, thought about that word: okay. It’s what people say when they want to skip the consequences.

“No,” I said. “But we’re honest now. That’s a start.”

He nodded. Didn’t argue. Just walked to the door, pausing with his hand on the frame.

“You’ve changed,” he said.

“No,” I replied. “You just never looked closely.”

Then he left.

That night, I didn’t write in the notebook.

I didn’t need to.

Some truths are loud enough to echo without being recorded.

They cleared out Lillian’s room in under an hour.

No ceremony, no staff gathering—just two aides, a rolling bin, and a checklist. The curtain stayed open the whole time. The sun hit the bed where she’d died two nights before.

By lunch, the room had a new name on the door. By dinner, a new woman had moved in. Her family brought a plant and a box of sugar-free cookies, and that was that.

The next morning, I asked if they’d kept any of Lillian’s things.

The nurse shrugged.

“No next of kin. Just a daughter somewhere in Tampa. Didn’t return our call.”

No memorial. No mention.

I waited until after dark and walked down the hall. Her door was open. New shoes under the bed. New photo frame on the dresser. A man in military uniform smiling beside a woman I didn’t recognize.

The teacups were gone. The crossword dictionary. The old scarf she wore even when it was warm.

Erased.

I went back to my room and locked the door.

I sat on the bed and let the quiet come. For the first time in weeks, I let myself grieve. Not just for Lillian—though her absence felt like a sudden gust in a room you thought was sealed—but for all of it.

For the friends long buried. For Harold. For the version of me who used to walk into grocery stores and not be followed by someone’s hand on my elbow.

I thought about the money, the trust, the plans, and I realized I hadn’t once asked myself what I wanted.

I’d only thought about what I could fix. What I could reclaim. Who I could teach a lesson to.

But Lillian never wanted to teach anyone anything.

She just wanted peace. Her own room. Her own tea. A name that meant something when she said it out loud.

Was that what I wanted?

Was I building a future, or just dressing up the ruins?

The next morning, I made a list.

Things I no longer needed: revenge. The last word. Apologies that would never come.

Things I still wanted: a window I could open without permission. My own spoon. My own mug. My own key. Quiet—not the kind that feels like abandonment, but the kind that feels like choice.

I canceled the call I’d scheduled with Andrew. Postponed it a week. I needed to sit with these thoughts a little longer. Let them settle into something real.

That afternoon, Sandra asked me if I wanted to join a new group activity.

“Painting,” she said. “Therapeutic.”

“No,” I replied.

“Still not your thing?” she asked.

“I’m choosing what is,” I said.

She gave me a look. Not cruel. Just confused—as if the idea of an old woman choosing anything beyond pudding flavors was foreign.

I didn’t explain.

Later, I visited the back garden and sat on the bench where I’d first met with Andrew. The leaves were starting to turn—late-season gold, a few brittle reds. The sky was quiet.

I reached into my pocket and found a tea bag. Lillian’s. One of the good ones.

I brewed it that night. Slowly. Poured it into the thick ceramic cup they gave me when I first arrived—the one with the chip on the handle that nobody else wanted.

And I drank it.

Not for comfort.

For clarity.

They called from the legal office on Tuesday morning.

“Mrs. Leland,” said Carla’s calm voice, “the court has set a date for the hearing to revoke your son’s power of attorney. Thursday next week. You’ll be transported under legal escort.”

I thanked her and hung up.

Then I sat with it.

That word, escort. Like I was some delicate parcel being fed through danger. Maybe I was. Or maybe I was just a woman who finally had something they couldn’t take away. Not the money. Not the house.

Not even her silence.

That afternoon, I found Hilda in the hallway, watching the elevator like it might open on something that could change her life.

“Going somewhere?” I asked.

“Only in my head,” she replied.

I walked with her back to her room. We didn’t talk much. She was one of the few people who understood that quiet wasn’t a lack of something. It was sometimes the only space you had left to think.

Before I left, I pulled something from my pocket. It was a folded envelope.

“What’s this?” she asked.

“A name,” I said. “A lawyer. You don’t have to use it. But if you ever feel like someone’s taken too much from you, call.”

She looked at me for a long time, then tucked it into the drawer beside her rosary and bottle of aspirin.

I didn’t say goodbye.

Neither of us would have liked that.

Back in my room, I opened the notebook again—not to make another list, but to write something down I hadn’t dared admit.

If I leave with bitterness, they’ve still won.

If I leave with silence, I get to decide what it means.

If I leave with peace, I take back my name.

It wasn’t a mantra. It wasn’t a plan.

It was just a truth.

The next day, I asked the nurse for a staff envelope.

“I want to send something,” I said.

“To who?” she asked.

“My granddaughter.”

She hesitated.

“You can call her, you know.”

“I want her to have this on paper,” I said.

She brought the envelope. I wrote Rosie’s name across the front.

Inside, I put three things: a copy of the trust document with her name on it; a photo of me and Harold standing in front of our first house in 1963; and a handwritten letter—four pages.

I didn’t reread it. Some words don’t need editing when they come from the core.

I sealed it and gave it to the nurse.

“Mail it today,” I said. “Not tomorrow. Today.”

“Okay,” she replied, curious. But she didn’t ask.

That night, Thomas called again. Voicemail again. His voice was smaller now.

“Hey, Ma, just checking in. I know I haven’t handled everything right. I guess I’m still figuring things out. Call me when you can.”

He didn’t say, “I love you.”

Not even at the end.

I didn’t call back.

Instead, I opened the last drawer of my little dresser. Inside was the original lottery ticket. The paper had faded slightly, the edges soft from handling.

I held it for a while.

Then I tore it in half. Then in half again. And again, until all that remained were small squares that looked like snow.

I dropped them into the waste bin without ceremony.

Not because I regretted it.

Because I didn’t need it anymore.

The money was real. The trust was real. But the ticket had only ever been a door.

And I was already on the other side.

The courtroom was small, not like the ones on television. No grand wooden benches or cameras waiting outside. Just a few rows of seats, a table with mismatched microphones, and a judge who looked like she’d seen too many people lie and too few tell the truth.

I sat in the front beside Andrew. My hands were steady. My coat was clean. My shoes were the ones Rosie gave me for Christmas three years ago. I’d kept them in a shoebox marked FOR BETTER DAYS.

This counted.

Thomas sat across the aisle, lips pressed together like he wanted to say something but couldn’t find the right tone.

Good.

Let him search.

Marsha wasn’t there. Probably advised to stay away.

Probably smart.

Andrew leaned toward me.

“Stay quiet unless they address you,” he murmured. “You don’t need to defend anything. That’s my job.”

I nodded.

The hearing wasn’t long. Thirty-six minutes, all told.

Andrew presented the documents, the timeline, the medical statements, the financial activity on the joint accounts, the missing authorization letters, the furniture sold without consent, the home listing without signature.

“Mrs. Leland,” the judge asked me finally, “do you feel you were placed in care against your will?”

“Yes,” I said. “I wasn’t asked. I was told.”

“And the power of attorney,” she continued. “Did you fully understand what you were signing?”

“No,” I said. “Because I signed nothing. The papers were processed without my knowledge.”

Thomas shifted, opened his mouth. His lawyer placed a hand on his arm.

“And do you feel you are mentally and physically capable of managing your own affairs?” the judge asked.

“I do.”

“Do you have evidence of support for that claim?” she asked.

Andrew passed over the file. Inside: a signed statement from a state-licensed psychologist. Full cognitive assessment. No signs of dementia. No signs of diminished capacity.

The judge flipped through it slowly.

Then she looked at Thomas.

“Your client claims he acted in good faith,” she said to his lawyer. “But financial good faith includes transparency, which was clearly absent.”

Thomas said nothing.

She turned back to me.

“Mrs. Leland, are you requesting full revocation of the existing power of attorney?”

“Yes.”

“And replacement?” she asked.

“No.”

There was a pause.

“You don’t wish to assign it to another family member? A third party?”

“I wish to hold it myself,” I said.

Another pause. Then she nodded.

“Request granted.”

Just like that.

Gavel. Stamped order. A paper slid down the bench toward Andrew.

It was done.

I didn’t cry. Didn’t sigh. Just sat still while the weight shifted.

Outside, Thomas followed me down the courthouse steps.

“Ma, wait,” he called.

I stopped. Turned.

He looked thinner in daylight. Less sure. Less correct.

“I didn’t mean to hurt you,” he said.

“But you did,” I replied.

“I thought I was doing the right thing.”

“No,” I said. “You thought you were the only one who could.”

He opened his mouth. Closed it.

“I don’t want the money,” he said suddenly. “I never did.”

I smiled.

“That’s good,” I said. “Because now you’ll never touch it.”

He blinked.

I stepped closer.

“Just enough,” I said. “You treated me like a phase to be managed, a thing to box up. But I raised you. I paid for your braces. I stood outside your school concerts, even when your father couldn’t leave work. I taught you how to tie your shoes and how to sign your name.”

I paused.

“And now I’m teaching you how to lose.”

Then I walked away.

I didn’t look back.

Not once.

If you’ve ever been silenced, ignored, or tucked away like a folded coat, read this to the end. And when you’re done, say something—even if it’s just to yourself.

I left Rose Hill on a Tuesday morning.

No one noticed.

Andrew had arranged everything. A nurse signed the transfer papers: TEMPORARY LEAVE FOR INDEPENDENT REASSESSMENT OF LIVING NEEDS.

No questions. No fuss.

I packed two bags—one with clothes, one with papers. The staff gave me a generic hug.

“Don’t forget us,” Sandra said.

“I won’t,” I replied.

It wasn’t a lie. I just wouldn’t remember them the way they expected.

The car was waiting outside. Black. Quiet. No logos.

I didn’t say goodbye to Hilda. I’d already left something under her pillow: a note, unsigned, with the lawyer’s number and a line from Lillian.

To the day no one asks where you’re going.

The drive was long. I didn’t speak. The driver didn’t ask. I watched the trees change, the roads widen, the landscape shift from strip malls to quiet hills and low water.

We pulled into a narrow street with no signs. At the end, a small white cottage with blue shutters.

Mine.

I walked through the front door and took off my shoes. The floor was cool, clean. It smelled like new wood and sea salt.

On the counter was a teapot already waiting.

Andrew had thought of everything.

In the living room, one chair, one lamp, one window. It faced the water. No television. Just silence.

The kind you choose.

That evening, I made tea and wrote the first line in a new notebook.

I was never small. Just made to feel that way.

I didn’t write anything else.

I didn’t need to.

That night, I slept without a lock on the door. Without someone checking if I’d taken my pills. Without Thomas’s name on my bank account. Without Marsha’s voice in my ears.

I slept.

And in the morning, I woke up when I wanted, made toast with too much butter, sat in the sun, opened the window, and remembered the sound of my own breath.

If this story made you feel something, share it. Leave a comment. Send it to someone who still thinks they have no voice.

Because someone out there needs to hear what I’ve finally said.

You are not a burden.

You are not finished.

And no one—no one—gets to lock you away and call it love.