I walked into my son’s backyard and heard, “Why is she even still alive?” I didn’t leave. I went on.

I heard it with my own ears.

“Why is she even still alive?”

The laugh that followed wasn’t loud, just sharp enough to split something deep in me. I stood behind the wooden gate, holding a glass dish of peach cobbler, still warm. My hands didn’t tremble.

Not yet.

I didn’t leave.

I walked through that backyard like I hadn’t heard a thing. Past the string lights. Past the picnic tables. Past the faces that didn’t turn toward me.

Some of them were my blood, some were strangers, but none of them smiled.

Someone cleared their throat.

“Oh, Mabel, we didn’t know you were coming.”

That was Jodie, my son’s wife.

The same voice from behind the fence.

“I brought cobbler,” I said.

No one offered to take the dish.

I found a spot at the far end of the table. The folding chair creaked under me. My back ached, but I sat up straight. The air smelled of grilled meat and citronella candles. Music played from someone’s speaker—something too loud and too fast for anyone over forty.

They laughed, ate, drank.

I watched.

Carl, my son, made a toast at one point.

“To family,” he said, raising a beer.

And when the glasses clinked, no one looked my way.

The children—my grandchildren—ran past me three times. No one stopped. No one said, “Hi, Grandma.” I wondered if they even recognized me without the apron or the grocery bags.

I used to bring them gummy worms in Ziploc bags.

Jodie eventually approached. She leaned in with that tight-lipped smile she wears when cameras are around.

“Did you want a plate?”

I looked up at her. “I’m fine.”

She nodded too quickly and walked away before I could say more.

I stayed until the end. I helped stack plates. I folded napkins. I wiped the sticky table with a damp paper towel while the others started moving indoors.

Then I picked up my empty glass dish, still warm from the afternoon sun, and I left.

Not in anger. Not in sorrow.

But with a decision.

The next morning, I made coffee in my smallest pot. Just one cup. I sat at the table by the window—the same table where Carl used to do his homework. Legs too long for the chair.

Back then, he needed me.

Now, he just tolerated me.

Barely.

I didn’t speak to anyone that Sunday. The cobbler dish was clean, dry, and put away. I left the house once to bring in the mail, but I didn’t open the envelopes.

I wasn’t ready to see his name on the electricity bill again.

That house—their house—was mine once. The down payment at least. Forty thousand dollars from my retirement account back when I believed in second chances and “family investments.”

“Just to help you get started,” I’d said.

No strings.

Apparently no place at the table either.

The paperwork was still in my filing cabinet. I’d never needed to look at it before. But now I wanted to see.

Not the numbers. I knew the numbers.

The names.

Whose name was on what? Who truly owned what I’d given?

I pulled out the folder labeled CARL – HOUSE. Inside, I found the purchase agreement, the deed, the signed letter I’d written, gifting the money with no expectation of repayment.

“Because you’re my son,” I had written.

It hurt to read that line.

More than I expected.

That evening, I called a woman named Lena. She’s not a friend. Not exactly. But she’s sharp. Used to work in probate. We met at bridge years ago and stayed in occasional contact.

I told her I had questions about property, gifts, and estate documents.

She didn’t ask why. She just said, “Come by tomorrow. Bring everything.”

I slept well that night. No pills, no pacing.

Not peace exactly, but a kind of alignment.

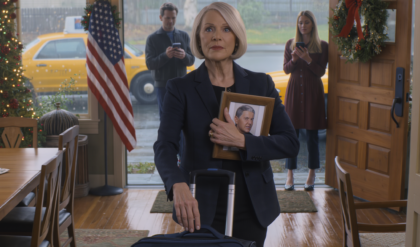

In the morning, I dressed carefully—ironed slacks, real shoes, the good coat, even though it was too warm for it.

When you’re about to change the shape of your life, you wear something with buttons.

Lena’s house smelled like lemon cleaner and peppermint tea. She looked at the folder, skimmed the documents, and gave a small grunt.

“No written expectations. No shared title. It’s theirs now. You gifted it.”

“I know,” I said. “But that doesn’t mean I’m powerless.”

She told me what could still be done about accounts, wills, powers of attorney.

“You can’t take the house back,” she said. “But you can make sure they don’t get anything else.”

That was enough.

She gave me a checklist. I folded it in half and put it in my purse.

That evening, I sat back at the kitchen table. No music. No television. Just the silence I used to hate, but now welcomed.

I took a blank sheet of paper and wrote a name at the top.

CARL.

Then I drew a single line through it.

On Wednesday, I baked a pie I didn’t intend to share. Blueberry with a little lemon zest. I used the good crust recipe, the one I used to reserve for birthdays and Thanksgivings.

This time it was just for me. No reason. No occasion.

Just because I still could.

I sat on the porch while it cooled, my knees covered with the old afghan Doris gave me before she passed. The street was quiet, a few kids on bikes, someone mowing a lawn two houses down.

It was the kind of afternoon where nothing big happened.

Unless you were watching closely.

Around four, a car I recognized pulled into the driveway across the street. Jodie’s sister, Michelle, stepping out with a tote full of groceries and a bottle of wine. She knocked once and went inside without waiting.

Comfortable. Certain of her place.

I hadn’t been invited to that house in nearly four months—not since Ruby’s birthday. Even then, they sat me near the trash bin.

“So you won’t be too close to the music, Mom,” I remember Carl saying that like it was thoughtful.

Ruby hadn’t opened my gift until after I left. A picture book, hand-stitched. I’d written a little note inside the cover.

“To Ruby, with all the love a Grandma can fit on a page.”

She never mentioned it.

I’d seen them twice since.

At the grocery store once. Carl in a rush, Jodie pretending not to notice me in the produce aisle.

Another time at the library, where Ruby walked right past me. No smile. Just a glance, like I was a substitute teacher or a neighbor she couldn’t quite place.

And still I’d kept a drawer in my hallway with stickers, tiny notebooks, little treasures for the children—just in case.

For years I filled it faithfully.

That day, I emptied it.

Every last thing went into a paper bag. I set it by the curb with the other recycling. I watched the bag sit there for hours, untouched.

Just like me.

That evening, I got a message from Carl.

“Hey, Jod says she might have hurt your feelings on Sunday. Didn’t mean anything by it. She was just tired. You know how family events can be.”

I read it twice.

Then I deleted it.

Not replied.

Deleted.

I wouldn’t archive his explanations like museum pieces anymore. I’d done that too long—stored excuses like mementos, wrapped them in the soft padding of he didn’t mean it or she’s just under stress.

No more.

At seven, someone knocked. For a second, I thought maybe—but it was Kay from next door, bringing a container of lentil soup and asking if I’d seen her cat.

I hadn’t, but I invited her in.

We sat at the kitchen table and split the pie. She didn’t ask about Carl. Didn’t ask why my eyes looked heavier than usual.

She just said the pie was so good it made her knees hum.

We laughed.

I needed that laugh more than I realized.

Later, after she left, I picked up a photo from the shelf in the hallway.

Me and Carl, 1987. He was eight, missing a front tooth, smiling like I was the whole world.

I looked at that boy and whispered, “I miss you. Not the man. The boy.”

I turned the photo face down.

Then I opened my desk drawer and removed the envelope labeled LEGAL.

In it: my will, my medical directives, the durable power of attorney Carl had signed on for three years ago when I had the fall. The one he never followed up on. Never asked about.

I held that document in my lap a long time.

Tomorrow, I’d go back to Lena.

But that night, I sat still in the dark and said goodbye to a version of my family that only existed in my memory.

Lena’s office was quiet the next morning—a soft sort of quiet, the kind that wraps around you like a thick scarf. Her desk was lined with neatly stacked files, a mug that said I READ CONTRACTS FOR FUN, and a glass jar of peppermints no one ever seemed to touch.

“I want to start with the power of attorney,” I said, placing the document in front of her. “Revoke it today.”

She looked at me over the rim of her glasses.

“Are you sure, Mabel? That’s a big shift.”

“I’m sure.”

She didn’t ask why. Just nodded and slid the paper toward her side of the desk.

“We’ll file the revocation today. I’ll notarize it. You’ll need to sign a few things, but I’ll make it easy.”

I sat back as she printed the forms. My heart didn’t race. I wasn’t trembling.

This wasn’t revenge.

This was repair.

“I also want to adjust the will,” I said. “Remove Carl as executor. Remove him completely.”

That gave her pause.

“You want to cut him out entirely?”

I nodded.

“He has a house, a job, a family. He doesn’t need what I’ve saved. He’s already made clear what he values.”

She didn’t argue. Just opened a clean template and began typing.

“Who should take his place?”

“I’m not sure yet,” I admitted. “But I’ll find someone. A professional, maybe. Someone who doesn’t look through me like I’m a loose end.”

She made a note.

“And the house?”

“The house goes to no one in the family,” I said. “Sell it. The proceeds should go to a cause that matters.”

“Any ideas?”

I reached into my purse and pulled out a worn brochure. The women’s shelter on Greenway Avenue.

“I stayed there once, long ago. Before Carl was born.”

She didn’t say anything for a while. Just clicked a few boxes on her screen.

“You’re very clear about this,” she said.

“I’ve been unclear long enough.”

When the documents were ready, I signed everything in careful, deliberate strokes. She notarized them, stapled them neatly, and handed me a copy of each.

As I stood to leave, she walked me to the door.

“If you change your mind, any of it, just call.”

“I won’t.”

The air outside felt sharper than before. The sun was out, but it didn’t matter.

Some days you carry your own weather.

I pulled my coat tighter and walked slowly back to my car.

At home, the phone was blinking. One message.

“Hey, Mom. Got your voicemail about legal stuff. Not sure what’s going on. Jodie said you were acting weird last weekend. Anyway, call me, okay.”

I deleted it.

Then I blocked the number.

The next morning, I called a locksmith.

The man was young, polite. He replaced the front and back door locks without question. When he handed me the new keys, I made four copies.

One stayed in my purse. One in a fireproof box. One with Kay next door. One for my safety deposit box.

I slept better that night.

No dreams.

Just rest.

Saturday morning came with the smell of rain—not the dramatic kind, just that soft metallic damp that settles into the edges of things.

I pulled on my boots and went outside anyway.

The garden hadn’t been touched in weeks, and the marigolds were leaning like tired shoulders. I clipped them back slowly, methodically. The shears in my hand felt like control.

At noon, I drove to First Mutual Credit Union. The branch was quieter than I remembered. No long lines, just the low hum of printers and the polite chatter of customer service voices.

I asked for a manager.

A woman named Trina came out, brisk but kind, and led me to her glass-walled office.

“I’d like to review all authorized users on my accounts,” I said.

She pulled up the screen.

“You have one co-signer and one authorized card holder listed. Carl J. Hemsworth. That your son?”

“Used to be.”

She hesitated.

“Would you like to remove him?”

“I’d like to erase him.”

Her fingers paused above the keyboard.

“Completely?”

“Yes. Remove the access, cancel the card, reissue everything in my name only. And I’d like to set new security questions, change the online login, and lock the account until I come in personally.”

She nodded and began typing.

While she worked, I stared at the plant on her desk. A pothos, its leaves glossy and heart-shaped, trailing gently toward the floor.

I used to have one just like it in Carl’s nursery. He once tried to eat the dirt. I’d laughed so hard I nearly dropped the diaper bag.

Trina printed out the changes and slid the papers to me.

“If you’d like to set up alerts or create a trust, we can help with that too.”

“Not yet,” I said. “I’m still building the next version of my life.”

She smiled like she understood more than she said.

When I left the bank, I didn’t feel triumphant.

I felt clean.

At home, I went to the hall closet—the one with the photo boxes, the holiday tablecloths, and the quilt I never finished. I took out the fireproof lock box and opened it.

Inside were my most important documents. The deed to the house, birth certificates, insurance policies.

I removed Carl’s birth certificate.

Not to destroy it. Just to separate it.

I placed it in a folder labeled HISTORY and stored it in a drawer away from everything else.

That night, I opened my address book. It still had tabs from the nineties, little plastic dividers that had yellowed over time.

I flipped to C and stared at the names.

Carl and Jodie.

Ruby and Trent.

I took out a pen and drew a single line through each one.

Then I flipped to L and wrote a new name.

Lena Moore – Attorney, Trust & Estate.

I slept with the windows open that night, the rain making soft percussion on the roof.

No nightmares.

Just a quiet, steady knowing.

Sunday, Kay came by again, this time with banana muffins. We sat in the kitchen and talked about the stray cat that had taken up residence under her porch. We named it Vernon for no good reason.

She stayed until just after lunch.

After she left, I picked up the Sunday paper and read it cover to cover. I underlined a listing for a small apartment in a quiet complex on the edge of town.

Two rooms. Ground floor. Washer and dryer included.

Just enough.

I clipped it out and set it on the fridge. Not for now.

But for soon.

I wasn’t running.

I was preparing.

Because the next time someone asked, “Why is she even still alive?” I wanted the answer to be clear.

To reclaim everything I gave away too cheaply.

On Monday, I called the real estate attorney Lena recommended, a man named Charles Lindell. His voice was steady, low—the kind you trust before you even meet the eyes behind it.

I told him I wanted to talk about title changes and property transfers. He gave me an appointment for Thursday.

In the meantime, I gathered everything. The deed to the house, the property tax records, the repair invoices I’d kept for twenty years. New roof, new plumbing, the furnace that Carl had said wasn’t worth the investment, but I’d paid for anyway.

Every receipt was a thread in the story they wanted to forget.

I made neat copies. I labeled folders.

When I was finished, my dining table looked like the war room of a woman no one had expected to resist.

That night, the phone rang again. Blocked number.

I let it go to voicemail.

A moment later, the machine picked up.

“Mabel, it’s Jodie. Look, we really don’t understand what’s going on. Carl’s been trying to call. Ruby’s been asking about you. We’re all worried. Please call us back.”

I turned off the machine.

The lie sat in the air like old perfume.

Ruby hadn’t said a word to me in weeks, not even on my birthday, which came and went with nothing but a Facebook notification from Jodie that said, “Hope you’re having a great one,” beneath a photo of their dog.

It was the same birthday where I sat in my kitchen alone and made myself a single cupcake just to mark the day.

They weren’t worried.

They were unsettled.

And there’s a difference.

On Thursday, I put on my navy cardigan, the one with the mother-of-pearl buttons that still shined when I held them up to the light. I arrived at Charles Lindell’s office twenty minutes early.

His receptionist offered me coffee. I declined.

My hands didn’t need caffeine that day.

Charles was kind in a quiet, intelligent way. The kind of man who listens more than he speaks.

I liked him immediately.

“I want the house to be in a trust,” I said once we were seated. “No one in my family has access. Not now, not later.”

He nodded.

“A living trust is straightforward. You’ll be the trustee and the beneficiary for now. When you pass, it can go wherever you choose.”

“I want it sold. Everything liquidated. The proceeds go to the Greenway Women’s Shelter in full.”

He raised an eyebrow.

“No family inheritance?”

“No.”

He didn’t push. Just wrote it down.

“I also want to remove Carl from any and all documents where he might be listed as a beneficiary. Bank accounts, insurance, health care proxies. All of it.”

“I’ll prepare the documents,” he said. “We can notarize them in-house. You’ll need to update your will to reflect these changes, too.”

“I’ve already started that with my estate lawyer.”

He smiled, a small curl at the corner of his mouth.

“Then we’re just making it official.”

We worked for nearly two hours reviewing clauses, signing forms, assigning contingencies. He explained everything with patience and precision.

When we were done, he handed me a slim binder.

“This is your trust packet,” he said. “Keep it safe. Everything else we’ll file this week.”

I thanked him and left the office with a strange sense of solidity, like my spine had real weight again.

On the way home, I stopped by the bakery on Main Street. I hadn’t been in years. The girl behind the counter was new. She called me ma’am and gave me a free cookie for “being lovely.”

I bought a lemon tart and ate it in the car, the sunlight warm on my knees through the windshield.

At home, I sat in the quiet and reread the trust documents.

My name. My signature. My terms.

No loopholes. No weak spots.

For the first time in months, maybe years, I didn’t feel like someone waiting to be chosen.

I had chosen myself.

Later that evening, just as the sky began to turn, a car pulled into my driveway.

Carl.

He stepped out slowly, like he wasn’t sure if he’d be welcomed.

I didn’t open the door.

He knocked once, then again.

Finally, he called through the door.

“Mom, please. I don’t know what’s happening.”

I sat on the couch, hands in my lap.

“You changed the locks. You blocked my number. I just want to talk.”

He sounded less angry than uncertain, like someone trying to find the map after realizing he’s no longer holding the pen.

“Just tell me what’s going on.”

I didn’t answer.

After a while, he left.

I waited ten minutes before I stood. I watched him from the window as he backed out slowly, his face tired behind the wheel.

Then I sat back down and poured myself a cup of tea.

Sugar. No milk.

My mother always said, “If they don’t hear you softly, they’ll hear the silence louder.”

The front yard hadn’t looked this tidy in years.

On Friday, I trimmed the hedges, swept the porch, even replaced the cracked bulb above the door.

Not because anyone was coming.

Because I was leaving, eventually, and I wanted the house to know I hadn’t stopped caring.

It wasn’t the house’s fault.

I’d lived in it for forty-three years. Moved in when Carl was five, back when his favorite thing was to line up his toy dinosaurs along the windowsill and name them like classmates.

“This one’s Rebecca and this one’s Mrs. Fulton.”

It had been my dream house once. Three bedrooms, a wide front window, a narrow little attic I turned into a sewing room.

I’d painted every wall myself. Tiled the kitchen floor after Frank died. Learned how to replace the gutter screens when the neighbors said I should just wait for my son to help.

I stopped waiting a long time ago.

That afternoon, I walked through each room with a notepad.

In the guest room, an old dresser I’d once offered to Carl and Jodie when they needed furniture.

They said it was too “dated.”

In the hallway, a framed cross-stitch from my sister that said PEACE LIVES HERE.

It had been hanging so long the wall behind it was cleaner than the paint around it.

In the back bedroom, Carl’s old room, the curtains were still the ones with little sailboats. I’d meant to replace them years ago, but something always got in the way.

The closet still held a dusty box of baseball cards and a shoebox labeled PRIVATE.

I didn’t open it.

Instead, I sat on the edge of the bed and looked out the window.

The apple tree in the backyard was crooked now. Time had pulled it leftward, but it still bloomed each spring, defiantly, like it didn’t know it was tired.

I stayed there for almost an hour, remembering the time Carl climbed that very tree and got stuck, wailing like a siren until I came out barefoot and furious, dragging the ladder behind me.

The way he hugged me afterward, shaking with leftover tears.

“Don’t tell anyone,” he said.

And I never did.

I remembered the first time he came home with Jodie. The way she looked around my house like it was a motel that hadn’t been reviewed yet.

“It’s cozy,” she’d said.

I remembered holding Ruby for the first time, her cheeks red and crumpled. Carl had actually cried that day.

“She’s perfect,” he whispered.

I remembered the Christmas when Jodie told me not to bring food because “the kids don’t eat old-fashioned stuff,” and how I brought a pie anyway.

Ruby never touched it. Trent said it tasted like soap.

They laughed.

That was the year I stopped baking for their holidays.

But I never stopped baking.

I stood up and wrote on my notepad.

Leave the curtains.

Take the quilt.

In the kitchen, I opened the cabinet above the stove.

My baking cabinet.

Everything still in its place. Vanilla. Cinnamon. Brown sugar. The heavy measuring cups Frank bought me for our tenth anniversary.

I wrapped them carefully and placed them in a padded box labeled KEEP.

The next day, I called the apartment complex I’d clipped from the paper. A kind woman named Teresa answered.

“Yes, we have a one-bedroom still available,” she said. “First floor, lots of light, and it’s quiet. Mostly retirees and teachers.”

“Do you allow cats?”

“We do.”

I don’t have a cat, but I liked knowing I could.

I scheduled a viewing for Tuesday.

That night, I sat on the porch with a blanket and a mug of tea. The street was still, a few porch lights across the way, a wind chime tinkling faintly next door.

I thought of all the nights I’d sat here waiting for headlights, for footsteps, for someone to remember I existed.

But not this night.

This night I was just sitting.

No expectation. No hunger.

Just me in the cool air with my name still mine and my home still quiet.

I thought about Carl.

I didn’t miss him.

Not exactly.

I missed the idea of him. The son who built Lego castles on my coffee table. The boy who held my hand too tightly crossing the street.

That boy had disappeared long ago, replaced by a man who couldn’t see past his own needs, his own schedule.

Maybe someday I’d mourn him properly.

But not now.

Now I had packing to do.

The call came on Sunday evening. Not from Carl.

From Ruby.

“Hi, Grandma,” she said. Her voice was smaller than I remembered. “Is this still your number?”

“It is.”

A pause.

“I found it in one of Dad’s old phones. He didn’t know I was looking.”

I waited.

“I wanted to say I’m sorry,” she blurted. “For the backyard. For everything, really.”

I didn’t rush to comfort her. That instinct—the one to shield others from their shame—had lived in me a long time, but I’d evicted it recently.

“What are you sorry for?” I asked gently.

She took a breath.

“For not talking to you. For pretending not to see you at the library. For laughing when Mom said what she said. It wasn’t funny. I just…” She stopped.

“You just wanted to belong,” I finished for her.

“Yes.”

I didn’t forgive her right away. That’s not how real apologies work.

But I did say, “Thank you for calling.”

“Can I see you?” she asked. “Just me.”

I thought about the pie drawer I’d emptied. The Christmas cards I kept sending even when they stopped arriving in return. The way she used to grip my hand when crossing icy sidewalks.

“All right,” I said. “Come by tomorrow after school. Just you.”

She exhaled like she’d been holding her breath all summer.

“I will. I promise.”

I hung up and sat quietly, my tea growing cold in my hands.

Monday came gray and drizzly—the kind of day that makes everything feel softer. I baked banana bread, not for anyone in particular, just to fill the house with something warm.

At 4:12, Ruby’s knock came. She stood on the porch in a hoodie two sizes too big and sneakers with the laces untied.

Her eyes were rimmed with something that wasn’t just mascara.

“I wasn’t sure you’d open the door,” she said.

“I wasn’t sure you’d knock,” I answered.

Inside, we sat at the kitchen table. She picked at the bread. I poured tea.

“Mom says you’ve gone crazy,” she said, not unkindly. “That you’re cutting us out.”

“I’m not cutting. I’m choosing,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

She nodded like she almost understood.

“I don’t hate you,” I added.

“I don’t hate you either,” she whispered. “I just… I think I copied how they acted. And I didn’t question it until I started missing you.”

The sentence folded something inside me.

“I want to come back,” she said. “If that’s allowed.”

I looked at her, this girl who still had the same eyes as Carl at eight, before the world taught him how to be unkind.

“You can come back,” I said. “But not for pie. Not for gifts. Only for truth.”

“I can do that.”

She stayed an hour. We didn’t talk about Carl or Jodie. Just school, books, a cat she wanted but wasn’t allowed to get.

She left with a second slice of banana bread wrapped in foil.

After she walked down the driveway, I watched her until she turned the corner.

I didn’t feel hopeful.

I felt honest.

That night, I wrote in my journal:

Maybe some doors don’t need to be slammed. Just gently locked from the inside, with a window left cracked for the ones who come alone and knock with care.

The next few days passed quietly. I packed slowly, one drawer at a time, one memory at a time.

Not because I was sentimental, but because I wanted to know what I was keeping and why. If something didn’t make me feel stronger, it didn’t come with me.

The apartment viewing was scheduled for Thursday afternoon.

That morning, I woke up early and brewed coffee strong enough to stand up on its own. I wore slacks and a blouse—not because anyone would judge me, but because starting a new chapter deserves clean seams.

The apartment complex was simpler than the brochure made it look, but it felt right. Brick buildings. Tidy flower beds. A bench under a linden tree.

Teresa, the manager, greeted me like she already knew who I was.

“Ground floor,” she said, unlocking the door to Unit 1B. “South-facing windows. Neighbors are quiet. Heat’s included.”

The space was small, yes, but honest. No pretense. No echoes of voices that had grown cold.

Just clean light and walls waiting for new stories.

I stepped into the kitchen and ran my hand over the laminate counter. It wasn’t marble.

But it was mine.

The stove had four burners, and the fridge hummed faintly, like it was keeping a secret.

“I like it,” I said. “I’ll take it.”

Teresa blinked.

“You don’t want to think about it?”

“I already have.”

By that evening, the paperwork was signed. I put down the deposit and scheduled my move-in for the first of the month.

Three weeks. Enough time to leave with care, not haste.

That night, I sat in the living room among half-filled boxes and wrote out a new address book card.

MABEL HEMSWORTH

128 Willow View, Apt 1B

No forwarding for Carl.

I smiled as I tucked it into my drawer.

Two days later, Carl showed up again. He didn’t knock right away.

I heard his car before I saw it, the engine idling for a while out front as if he was rehearsing something behind the wheel.

When he finally stepped onto the porch, I met him at the door.

I didn’t open it.

“You blocked me,” he said. Not angry. Just confused. “You changed everything.”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

I didn’t speak right away. I looked at his face, older than I remembered.

Or maybe I’d just stopped seeing him clearly years ago.

“I heard what Jod said,” I told him. “In the backyard. And I heard you laugh.”

He shifted.

“I didn’t mean it. You know how she is. She talks out of turn. It was a joke.”

“No, Carl. A joke has to have a punchline. That was just cruelty wrapped in silence.”

“I didn’t know you were there,” he muttered.

“That’s exactly the problem.”

He blinked.

“So that’s it? You’re erasing me over one bad afternoon?”

I wanted to laugh.

“One afternoon? The afternoon was just the final straw in a stack built over years. Years of being sidelined, pitied, ignored, tolerated. A life where I was convenient but never considered.

“I’m not erasing you,” I said. “I’m just finally choosing myself.”

He frowned.

“Ruby said you’re letting her visit.”

“I am.”

“So she gets a pass?”

“No. She asked to come back. You waited until your name started vanishing from documents.”

His face tightened.

“This is about money.”

“No,” I said. “This is about dignity.”

He looked past me into the hallway. Maybe he expected to see the old side table with his school photos still framed or the basket of holiday cards I used to keep.

But the hallway was clean. Clear.

“I’ll always be your son,” he said.

“And I’ll always be the woman who gave you more than she should have.”

I stepped back and closed the door.

Not slammed.

Just shut.

Through the window, I saw him linger a moment longer, then leave.

That night, I didn’t feel triumphant. I cried for seven minutes.

I timed it.

I let myself feel the break—not because I regretted it, but because endings deserve respect.

Then I made tea, folded one more box, and placed it by the door marked KEEP.

The kitchen table held only what mattered now.

One teacup. A lamp. A shallow bowl of oranges.

Everything else had been packed or donated.

I didn’t need much anymore.

Just what fit inside one small life.

On Sunday afternoon, I hosted tea for the first time in years. Not for birthdays or holidays.

Just for warmth.

Marcia came first with her limp and her bag of crossword books. Then Ida, in her fur-trimmed coat even though it was fifty-two degrees. Then Nora, my old friend from the church choir, who still wore perfume that smelled like early spring and old envelopes.

They didn’t bring food, though each had offered. I told them it wasn’t about that.

I baked a single spice cake. Nothing fancy. Just enough to slice once each, with one wedge left over.

We sat by the windows, the afternoon light soft and pale. I poured tea into my chipped china—the blue set that survived two moves and one accidental drop in ’94.

No one asked about Carl or Ruby or the house.

Instead, we talked about shoulder pain and grocery prices. Ida told a story about a bus driver who waited two extra minutes while she fumbled with her change. Marcia said her niece got engaged to a boy who wore socks with cartoon whales on them. Nora brought up the library’s poetry group and asked if we wanted to join.

It was the most comfort I’d felt in years.

At one point, the conversation dipped the way it always does when women over seventy drink warm things together.

The room quieted—not from awkwardness, but from fullness.

And I said it.

“I’m moving.”

Three sets of eyebrows lifted, but no one interrupted.

“I found a small place across town,” I said. “I’ll be gone by the end of the month.”

Ida leaned forward.

“Does your son know?”

“He doesn’t need to.”

Marcia nodded, as if that was all the explanation required.

They stayed another hour, helped wash cups, wrapped the extra slice of cake in foil, said they’d call soon.

When they left, the house was still.

But not empty.

I walked through each room again, this time not as a farewell, but as a blessing.

In the hallway, I stopped by the shelf where I used to keep framed photos of Carl’s family. Weddings. Birthdays. First days of school.

I’d already packed most of them away, unsure if I’d want to hang them again.

Except one remained—a picture of me and Frank, taken by a neighbor when we’d finished painting the front porch. We’re both covered in splatters, holding brushes like trophies.

He’s laughing. I’m squinting into the sun.

I took the photo and wrapped it in a kitchen towel.

It went into the box labeled ESSENTIALS.

Later that night, I opened my journal and wrote:

Three women drank tea in my kitchen today. No one interrupted. No one explained. No one corrected. We just existed together.

That entry meant more than all the Christmas newsletters I used to write, filled with pretend happiness and obligatory gratitude.

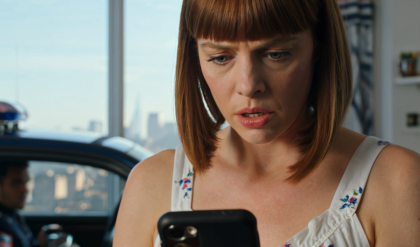

The next morning, I woke to a voicemail from Jodie. Short. Cold.

“I heard you spoke to Ruby, and Carl says you’ve been hostile. If this is your way of getting attention, it’s really sad.”

I played it once.

Then deleted it.

Hostile.

That’s what they called a woman who finally spoke up. That’s what they called silence when it no longer served them.

I opened the back door and stepped into the yard. The air smelled of wet leaves and the faint sweetness of old grass.

I walked barefoot through the patch of lawn I’d mowed myself for decades. At the far corner, where the garden used to be, the dirt was still dark.

I knelt slowly, ignoring the ache in my knees, and dug my fingers into the soil.

I planted three marigold seeds from an old paper packet I’d found while packing. Just three, not to bloom, but to mark something.

The doorbell rang at 10:42 a.m. sharp on Wednesday.

I knew it wasn’t the postman. He came at noon, give or take. And it wasn’t Kay, who knocked like she was always halfway apologizing.

No.

This knock was practiced.

Polite.

When I opened the door, Jodie was standing there in heels too high for the weather and a coat the color of wet bone. Her lipstick was perfect, but her eyes were tight.

“Mabel,” she said, like she was reading the word off a clipboard.

“Jodie.”

She didn’t ask to come in. She stepped past me like she still lived in the narrative where that was allowed.

I closed the door behind her.

Slowly. Deliberately.

She stood in the middle of my living room like someone preparing to deliver a pitch. Her hands clasped too tightly in front of her purse.

“This is getting out of hand,” she began. “You’ve blocked Carl. You’ve changed your accounts. Ruby is sneaking around to call you. And now I hear you’re moving.”

“All true,” I said calmly.

She blinked, thrown for a moment by the lack of resistance.

“We’re your family,” she said, putting weight on the word like it was an anchor. “You can’t just erase us because of a bad day.”

I studied her. The way she wore confrontation like jewelry—displayed, not felt.

“It wasn’t one bad day,” I said. “It was years of polite dismissal, of lukewarm invitations, of being tolerated instead of welcomed. One day just pulled the curtain back.”

Her jaw tightened.

“We never asked you for anything.”

“That’s the problem,” I said. “You never asked. You just expected.”

“I don’t know what Carl ever did to deserve this,” she snapped. “He’s a good man.”

“Good men don’t laugh when someone wonders why their mother is still alive,” I replied, my voice steady.

She took a step closer.

“You think you’re punishing him? You’re punishing Ruby. She’s confused, hurt, and you’re using her to prove some kind of point.”

That made me pause—not because she was right, but because of how easily guilt still knew my name.

I took a breath.

“Ruby came to me alone,” I said. “She’s sixteen. She knows what a closed door feels like.”

Jodie scoffed.

“You’ve always made things dramatic.”

“No. I’ve always made things possible,” I said, sharper now. “The down payment on your house. The babysitting. The casseroles. The last-minute rides. The silent endurance at birthdays when I was placed behind centerpieces so I wouldn’t ruin the aesthetic.”

She turned, pacing.

“You’re exaggerating. You’ve always been difficult.”

I smiled then, but not kindly.

“Is that what women become when they stop handing over their silence?”

Her mouth opened. Closed.

Then she spotted the packed boxes stacked near the front door.

“You’re really doing it,” she said.

“I am.”

“And what happens when you’re alone in that little apartment? When no one’s left to check on you? When Ruby forgets to call?”

“I’ll still have myself,” I said. “And I’d rather be alone with honesty than surrounded by people who flinch at my presence.”

She looked around as if the house might help her win, as if the walls might join in.

“You’re throwing everything away.”

“No,” I said, picking up the binder with my trust documents and placing it on the table. “I’m finally choosing what to keep.”

Jodie stood there a moment longer. Then she picked up her purse and walked toward the door.

Before she left, she turned.

“Don’t expect us to come running when you change your mind.”

“I’m not running,” I said. “And I won’t.”

The door closed behind her like punctuation.

Later that evening, Ruby texted me a single line.

She came home fuming. You okay?

I wrote back:

Perfectly.

Some doors need closing, Ruby. It doesn’t mean you’re on the other side.

She sent a heart emoji followed by, Still bringing cookies Thursday. Don’t bail.

I didn’t.

And I wouldn’t.

The papers were ready.

Lena called Thursday morning.

“Everything’s signed, filed, confirmed,” she said. “The trust is active. Your accounts are protected, and your will is updated. You’re now the sole decision maker of every inch of your life.”

“Thank you,” I said.

Two words that held more weight than most confessions.

“I’m proud of you, Mabel.”

I smiled into the phone.

“Funny how many people say that only after you start saying no.”

By noon, I was at the bank, binder in hand, handing over the final forms. The clerk was young, barely twenty-five, but she treated the documents like something sacred.

I liked that.

“We’ll update the beneficiaries right away,” she said. “And this authorizes removal of your son from all shared access.”

“It does.”

She nodded with the kind of calm efficiency I once mistook for coldness.

Now I understood.

She was simply prepared.

Like me.

Afterward, I walked two blocks to the post office and picked up a key for a new P.O. box. When they asked for a forwarding address, I declined.

Anyone who truly needed to find me already knew where I was.

Back at home, the afternoon light was soft through the curtains. I brewed a fresh cup of tea and pulled out the last envelope—my medical directive. A copy for my new doctor, another for the safe box.

It felt like sewing the final thread in a dress I’d been mending for years.

At 3:30, Ruby arrived. She brought chocolate chip cookies in a plastic container and a magazine with a quiz titled WHAT TYPE OF FLOWER ARE YOU?

We sat on the porch eating cookies and circling answers in pencil.

I was apparently a lilac—quiet, observant, easily underestimated.

Ruby was a marigold.

Resilient and hard to root out.

She read aloud, grinning.

“That checks.”

When the cookies were gone, we just sat. She swung her legs lightly under the bench.

“Dad says you’re turning your back on family,” she said.

I didn’t respond right away.

“He’s hurt,” she added, softer. “Not that it excuses anything, but it’s all he talks about.”

“Then he’s finally talking about something that matters,” I said.

She looked down at her lap.

“I miss the old you,” she said.

“No,” I said. “You miss the version of me who let herself be erased quietly. That wasn’t me. That was survival.”

She nodded.

“I get that now.”

We sat for a while longer. Then she pulled out a folded piece of paper.

“It’s just a sketch,” she said, suddenly shy. “I made it last night. I don’t know if it’s any good.”

I unfolded it.

A pencil drawing, rough but clear. A woman seated in a chair, her back straight, eyes forward. In front of her, a chessboard. On her side, just two pieces. On the other, a full set.

But her pieces were in winning positions.

“She’s not done,” Ruby said. “She’s just starting to play her game.”

I didn’t speak.

I couldn’t.

I reached out and squeezed her hand.

“Can I hang it in the new apartment?” I asked.

She lit up.

“Really?”

“Really.”

As the sky turned peach behind the rooftops, she stood to leave.

“I know this doesn’t fix everything,” she said. “But I want to be around, if you’ll have me.”

“I will,” I said. “But only as you are. No pretending.”

She grinned.

“Marigolds don’t pretend.”

After she left, I sat alone for a long time. The drawing in my lap, the house quiet around me, all the paperwork signed, all the decisions made.

No more permissions to seek. No more hoping for invitations that came too late or too shallow.

It was done.

Not bitterly.

Firmly.

Tomorrow I would begin packing the final boxes.

And after that, something better than hope.

Space.

Moving day arrived quiet, without ceremony.

I woke before dawn, made coffee in the same chipped mug I’d used for over twenty years, and stood in the kitchen one last time, barefoot, the linoleum cool under my soles.

The light hadn’t yet reached the windows, but I didn’t need it. I knew every inch of this house in the dark.

The movers came at nine sharp. Two young men, polite, fast, a little surprised by how few boxes I had. I’d labeled everything clearly: KITCHEN – KEEP, CLOSET – DONATE, BEDROOM – MEMORIES, and one marked DO NOT OPEN YET.

They didn’t ask questions.

By noon, the house was nearly empty. The walls looked tired, like they were exhaling.

I walked through each room slowly, my fingers grazing surfaces one last time.

Not to cling.

To thank.

In the hallway, I paused where Carl’s height marks used to be, long painted over. I could still feel the indentations if I pressed lightly enough.

Five years old. Seven. Eleven.

A lifetime of inches that couldn’t be undone.

I didn’t cry.

I placed a small envelope in the top drawer of the empty hallway table. It held one key and a note that simply read:

This house taught me everything. Thank you.

Then I locked the front door behind me and didn’t look back.

The apartment smelled like fresh paint and new beginnings. The movers placed the boxes exactly where I asked.

I tipped them too much. I didn’t care.

Teresa from the office brought me a welcome packet and a small plant.

“Something green,” she said. “For your windowsill.”

It was a tiny succulent in a ceramic pot shaped like a cat.

I placed it beside the kitchen sink and whispered, “I think we’ll get along.”

The first thing I unpacked was the kettle.

The second was Ruby’s drawing.

I hung it near the window, where the light caught it softly, the pencil lines glowing like they were freshly drawn.

That night, I made toast and ate on the balcony, wrapped in a blanket. No noise, just wind and the occasional hum of someone else’s television through the wall.

I didn’t feel lost.

I felt spacious.

The next morning, I unpacked the last box. Inside were the essentials: two dresses, a pair of shoes, a tin of buttons I’d collected over decades, and a letter folded in thirds, yellowed slightly at the edges.

Frank’s handwriting.

The letter he’d written me before his surgery—the one he didn’t survive.

If something goes wrong, don’t fold in. Stay open. Stay warm. Live with your hands unclenched. You have more strength than you know.

I placed it in the same drawer where I kept my will.

That afternoon, I baked for the first time in the new oven. Banana bread.

Again.

By now, more ritual than recipe.

As it baked, the whole apartment filled with a smell so familiar. I closed my eyes and smiled.

At four, Ruby arrived with her school bag and a fresh bruise on her cheek. Nothing serious—just the mark of a volleyball during gym, she explained.

“I brought jam,” she said, holding up a small jar. “Fig and something. I thought it sounded like you.”

We sat at the little table by the window, two pieces of warm bread between us. She spread the jam thick and slow, then looked up.

“Is this what peace feels like?”

“Not all of it,” I said. “But a corner of it, yes.”

She ate with both hands like she used to when she was small, crumbs trailing across the napkin. She told me about a boy in her class who’d drawn a beard on his mask and got sent to the principal’s office. About her English teacher who said “um” thirty-four times during one lecture. About how Jodie was furious with me for turning down a birthday invitation.

“She said you were making a spectacle of yourself.”

“I’m not making anything,” I said. “I’m simply not showing up where I’m not wanted.”

“I told her I wanted to come anyway. And she said she couldn’t stop me, but she wouldn’t drive me.”

“You walked?”

“No. I borrowed Grandpa’s bike. It’s in bad shape, but it got me here.”

That made me smile.

Frank would have liked that.

“You can leave it locked on the balcony,” I said. “We’ll fix it up together.”

Her eyes lit up.

“Really?”

“Really.”

After she left, I watched the sun lower behind the row of trees outside. I didn’t miss the house. I didn’t miss Carl’s silences or Jodie’s sideways smiles. I didn’t miss the old version of myself that whispered, Maybe next time they’ll see you.

Because now I saw myself.

And I didn’t need permission to exist.

One week after the move, the house sold.

The realtor called to say the offer came in just above asking.

“An older couple, no kids, looking for quiet and history,” she said.

I almost laughed.

They’d found both.

I didn’t go back. Not even for the walkthrough. I gave Charles power of attorney for the sale, signed what needed signing, and let it go.

He called when it closed.

“It’s done,” he said.

I thanked him, then hung up and stood in the middle of my apartment. It wasn’t large, but every inch of it was mine.

I opened a new bank account for the shelter donation. I didn’t put it in my will.

I gave it now.

I walked in myself, handed the check to the director, and said, “This is for the women who leave without shoes.”

She stared at the amount and started to cry.

I didn’t.

I’d done my crying.

This wasn’t grief.

This was intention.

That night, I made soup. Not for anyone, not for an occasion.

Just because I liked the way leeks softened in butter.

The radio played quietly in the background—some jazz station with no ads, just saxophones and soft rhythms that didn’t ask for applause.

I ate in my robe, standing by the stove.

No table setting. No explanations.

Just hunger met.

At around eight-thirty, my buzzer rang. I didn’t expect anyone.

When I answered, I heard Ruby’s voice.

“Can I come up?”

“Of course.”

She was carrying a shoebox and wore an oversized sweatshirt with sleeves pulled over her hands.

“What’s in the box?” I asked.

“Stuff I’m not ready to keep at home,” she said.

Inside: a notebook, a phone charger, a necklace that wasn’t Jodie’s taste, a photo of her and me at the zoo when she was five. She had chocolate on her face.

I’d forgotten that day.

She hadn’t.

“I don’t want to live there when I’m older,” she said suddenly, sitting cross-legged on the floor. “With them, I mean.”

“You won’t have to,” I said. “You get to choose.”

“Even if they hate me for it?”

“Especially then.”

She nodded, thoughtful.

“Do you think people can change?”

“Sometimes,” I said. “But I think the better question is, can they stop pretending?”

She looked up.

“Are you still angry?”

“No,” I said. “I’m finished.”

Ruby stayed until nearly ten. We didn’t talk about Carl. She didn’t ask for stories about him, and I didn’t offer.

Some threads don’t need tying.

When she left, she hugged me tighter than she ever had before.

The next morning, I walked to the corner store for milk. The man behind the register nodded at me like I was already part of the routine.

“You’re the banana bread lady,” he said. “The kid with the bike talks about you.”

I smiled.

“That’s me.”

I bought a newspaper just because I could and read it on the balcony with my feet tucked under me.

The world still turned.

Bills still came.

But the silence inside my chest was no longer heavy.

It was restful.

Later that week, a letter came. No return address, but the handwriting was Carl’s.

I opened it slowly.

Mom,

I don’t know how to fix this. I don’t know if you want me to. I said things I can’t unsay. I let things happen. I should have stopped. I don’t know how to be the man you deserve, and I’m scared it’s too late to learn.

But Ruby talks about you every day now. She’s different. Braver. And that came from you. I’m sorry. I hope one day you’ll let me try.

I folded the letter and placed it in a drawer.

Not forgiveness.

Not refusal.

Just a space where it could rest, undisturbed.

That night, I wrote in my journal:

I am not angry anymore. Not afraid. I am not waiting at windows, not watching porches. I am not a forgotten guest at someone else’s table. I am building my own.

The day I turned seventy-three, I woke up without an alarm.

There were no balloons, no surprise texts from relatives who remembered me once a year. No brunch reservations or gift bags left on stoops.

Just morning light through clean curtains, the sound of rain somewhere in the distance, and the soft breath of a life that now belonged only to me.

I made pancakes. Two of them. Ate them with honey and a sliced pear.

Then I sat in the middle of my little apartment with the photo of Frank propped on a chair and said, “Well, we got here, didn’t we?”

At noon, Ruby came. She brought tulips, red ones, still wrapped in the paper sleeve from the florist.

“You’re not a birthday cake person,” she said. “So I brought flowers, like grown-ups do.”

She gave me a small envelope. Inside was a card she’d made herself, painted, not drawn. On the front was a simple image: two chairs on a porch, one empty, one with a teacup on the armrest.

Inside it read:

Thanks for keeping a seat for me.

We had tea and toast and talked about her final exams, her plans to work part-time at the shelter over the summer, and how she was trying to convince her school to start a support group for kids who didn’t feel like home was home.

She asked me if she could use my name.

“Only if you use it for something true,” I said.

She laughed.

“That’s the only way I use it now.”

Before she left, she said, “You look different.”

“I feel different,” I replied.

She looked me over like she was taking inventory.

“You look like someone who doesn’t flinch.”

After she was gone, I sat on the balcony with a book I’d been meaning to read for fifteen years. I read three chapters, then put it down.

Not because I was tired.

Because I didn’t need to finish things just to prove I could.

The next day, I mailed a donation to a legal fund for older women in housing disputes. I didn’t include a note. Just the check and the name of the trust.

Quietly placed, like a stone in the right hand.

I also planted basil in a small clay pot. It wilted a little in the first days, then perked up, leaning toward the kitchen window like it had made a decision to live.

One morning, I got a text from Carl.

Happy birthday, Mom. I didn’t send a card. I figured I haven’t earned that yet. Just wanted you to know I’m still here.

I didn’t respond.

Not out of anger.

Because not every apology needs a reply. Some simply need to land quietly in the place where harm was once ignored.

That evening, I invited Marcia and Ida over. Nora couldn’t come—she’d caught a cold—but sent a crossword torn from her paper with a note.

12 down made me think of you.

The answer is ANCHOR.

We drank tea and laughed about knees and politics and how Teresa from the leasing office had taken up birdwatching in her hallway.

They brought cherry pie and a promise to come again next week.

After they left, I stood in the doorway for a moment and just listened.

Not for footsteps leaving or for silence returning.

For the sound of a home that had filled up again—this time with the right kind of noise.

That night, before I turned out the light, I wrote in my journal for the last time in that volume:

They asked why I was still alive.

Now I can answer.

To remember my name.

To set my own table.

To keep the door open just wide enough for those who knock with clean hands.